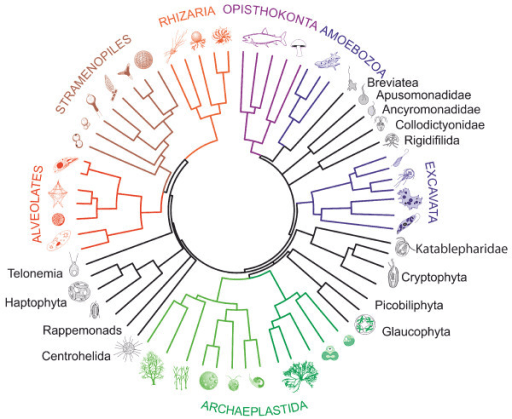

The fungal kingdom (Fungi) is related to the animal kingdom. They separated approximately 1.5 billion years ago.

Like animals and plants, fungi are eukaryotes, which means the cells contain cell-bound organelles and a nucleus. They are heterotrophic, like animals, but in contrast to most of them they exhibit external digestion. Like plants, they have vacuoles and a cell wall and reproduce both sexually and asexually. But in contrast to plants, the cell walls are made of chitin and glucans. Most fungi are multicellular, but there are also single-celled fungi, where yeasts are the most well-known.

Fungi building blocks

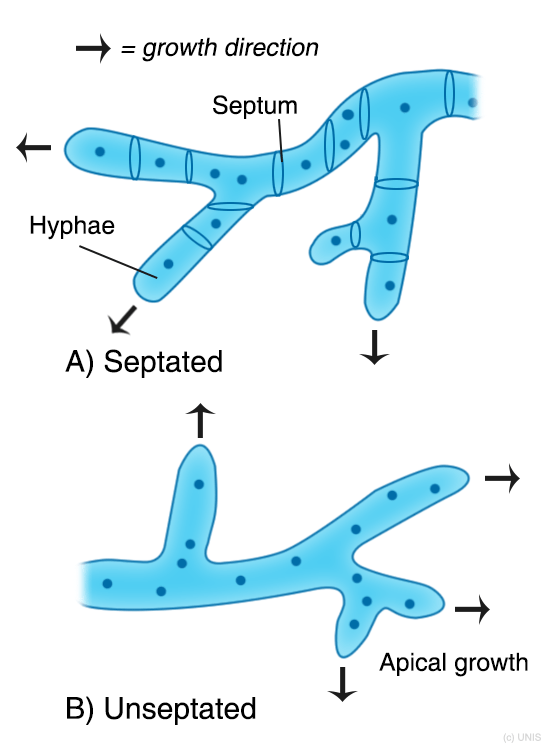

A typical fungus is built up of long, thin cells, the hyphae. As the hyphae are so thin, often smaller than 1/100 mm, a microscope is needed to study them. They have apical growth and branch into a dense network, called mycelium – the vegetative part of the fungus. The hyphae are protected by a cell wall of chitin and/or glucan. The mycelium can be septated (Ascomycota and Basidiomycota), or unseptated, (other fungal phyla). The content of the cytoplasm can move through pores in the septa from one hyphal compartment to another.

Dense mycelia can be seen by the naked eye, e.g. mould on bread, cheese or jam. Most often, however, the mycelia are hidden in soil or wood. However, difficult to see, it is supposed that a lump of soil of the size of a piece of sugar can contain as much as 10 km . The thin and branched hyphae have a large surface and are extremely efficient at absorbing nutrients. Some fungi lack mycelium, e.g. the budding yeast fungi and many chytrids, which consist of single, rounded cells.

Fungi are heterotrophic. This means that fungi cannot produce their own food by photosynthesis or chemosynthesis, but rely on organic compounds from plants, animals or other fungi for nutrition. They are unable to fix atmospheric nitrogen.

In contrast to animals, fungi utilise extracellular digestion (see animation above). Various enzymes are produced in the cytosol of the hyphae. They are transported with organic acids through the membrane of the hyphae and secreted into surrounding substrates. Depending on the enzyme, they can break down cellulose, hemicellulose, lignin, proteins or other complicated organic compounds to simpler soluble substances like sugars (mono- or disaccharides), amino acids or oligopeptides. These substances can be transported through the hyphal membrane into the fungal cell (hyphal compartment).

Fungi reproduction

What we usually see – and what customarily are called “fungi” – are the fruit bodies (sporocarps). They are produced when the fungus reproduces sexually. Sporocarps are, with very few exceptions, only produced by fungi belonging to either the phylum Ascomycota (sac fungi) or Basidiomycota (club fungi); ascocarps or basidiocarps, respectively. Most sporocarps are short-lived and are not necessarily produced every year, depending on yearly weather conditions (e.g. precipitation and temperature).

For fungi in the Arctic, the is late summer (late July to mid-August) or early autumn (mid-August to early September). Some wood-inhabiting fungi produce perennial sporocarps (e.g. the bracket fungi), however due to the lack of wood in the arctic they are quite rare.

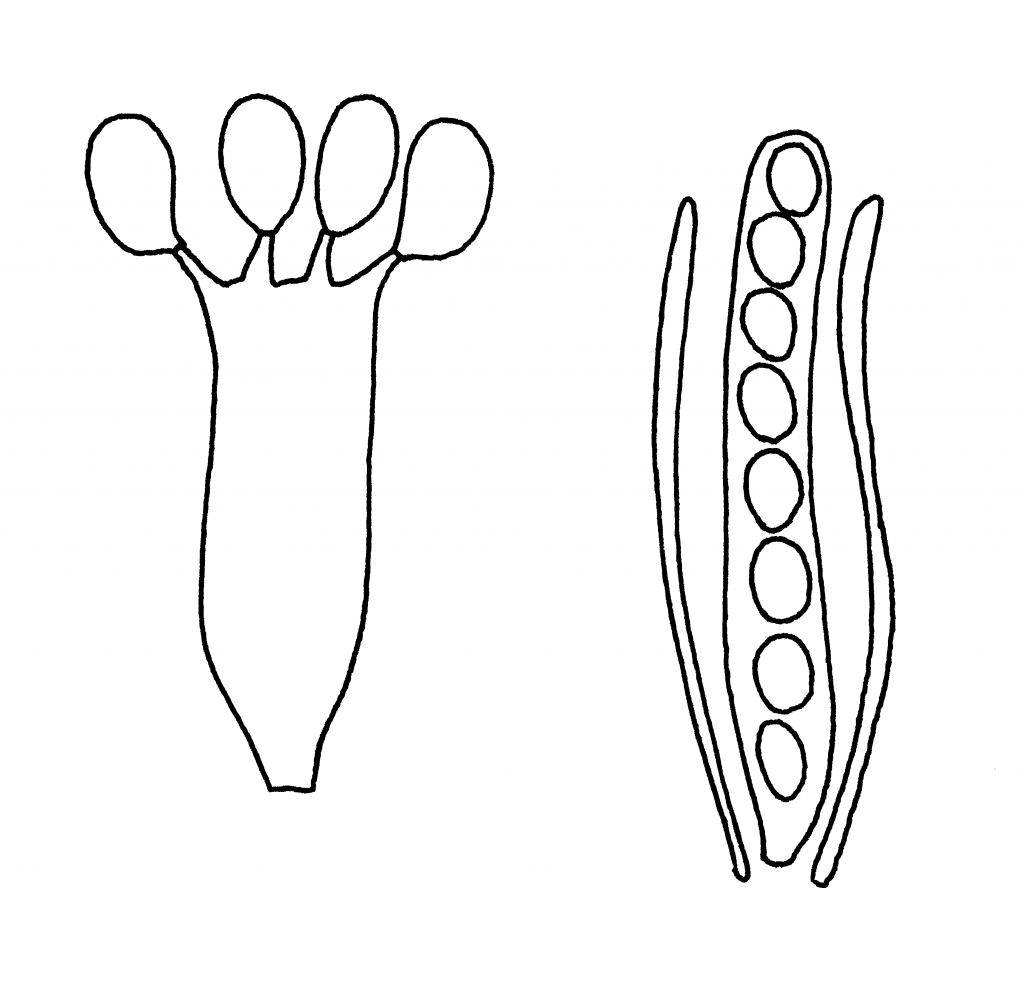

Sexual spores are produced on the sporocarps. The – usually 8 – spores (ascospores) of the Ascomycota are inside a sac-shaped sporangium, the ascus (plural: asci). The spores are released due to rising turgor inside the ripening ascus, and the spores are forced out of an opening on the top. Basidiomycota produce usually four basidiospores that sit on small stalks on top of basidium (plural; basidia). They are shed by a special snap mechanism which is still not exactly understood. Some Basidiomycota have basidiocarps with internal spores, which are passively released, e.g. puffballs.

Many fungi can also produce asexual spores by mitosis (mitospores or conidia). They are not normally produced on the sporocarps but directly on the mycelium, often from specialised structures.. Mitospores are common in many groups of Ascomycota, e.g. in moulds such as Penicillium, Aspergillus and Cladosporium. They are not so frequent in Basidiomycota.

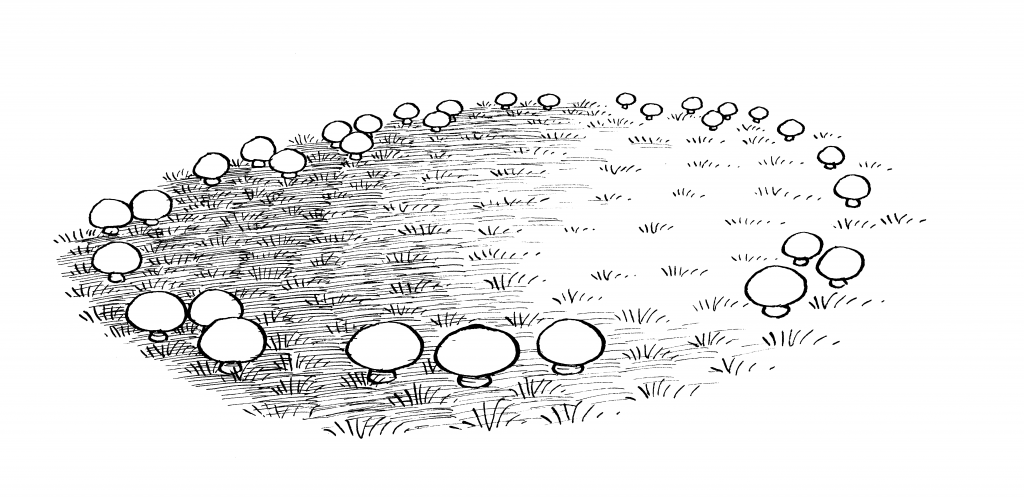

Fungi vary drastically in size. Some parasitic fungi live inside of plant cells or on pollen grains. On the other hand, in North America, there are giant fungi whose mycelia can cover several square kilometres and weigh up to 600 tons (more than three blue whales!). In the Arctic, Agaricus aristocratus produce fairy rings up to 50 m in diameter. All sporocarps in a ring belong to the same individual. The ring widens every year as the mycelium grows radially from the primary germination point.